Terry Wilcox

A month or so before

Richard Clark got out of prison, a friend of his from Terminal Island had been

released and had come to the Echo Park scene. He was skinny blonde guy, who

looked like a drawing in an R. Crumb cartoon, named Terry Wilcox. He’d been a

sailor in the Merchant Marine before getting busted in port and doing two years

for smuggling.

I remember going to

see him in the furnished room he was living in as soon as he got out. He seemed

to know his way around the social underbelly. He knew, for instance, where to

hide his greenbacks in a furnished room in a fleabag building.

Terry had one of the

most extreme minds I’ve ever encountered. He was almost illiterate. Notes and

other stuff that Terry wrote looked like they’d been written by a six-year-old.

He had a limited vocabulary and talked kind of charmingly dumb. But he was as

at home as hell with advanced calculus and physics and stuff, things that were way beyond my aptitude for mathematical

abstraction.

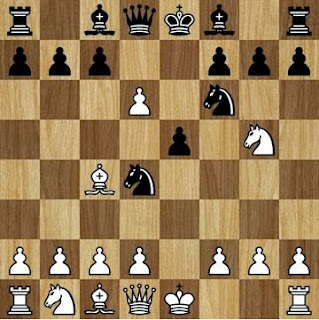

He’d spent his whole

stretch in the joint studying chess books. He told me that since he’d had a

broken foot when he’d gone in, he’d had the luxury of lying in his bunk all

day, instead of “doing one of their bullshit jobs they try to make you do.”

Once his foot had more or less healed, he’d continued with this inactivity,

only with chess books. He hadn’t actually resisted the guards, he told me. He’d

agreed with everything they’d told him, (“yes, boss.” “Sure thing, boss.”) and

then lay in bed reading chess books.

He could always beat

me at chess in less than eight moves. He called it the “fried liver” opening.

Apparently there was one way to counter it, which all chess crazies know, but

since I didn’t know it, it beat me promptly every time. Terry seemed to find

this amusing. What he couldn’t figure

out was why I couldn’t figure it out.

He had me take him to

Foster’s Blue Grotto to try to hustle somebody up to play him chess for money,

but that was, naturally, futile. It was fun to watch him try, though.

He linked up almost

immediately after he got out with the girl, named Chris, I was after at the

time. Oh, well.

He organised a

deep-sea fishing excursion out of San Diego once for himself and me. I drove us

down there. On the way we stopped at his parents’ house in a middle-class

subdivision in Orange County. His father was addicted to World War II

memorabilia. He and his dad seemed to get along great. There didn’t seem to be

any bad feelings about his time in Terminal Island.

The rest of the way

to San Diego he looked at the fishing reports in a newspaper. The word

“anglers” seemed to amuse him greatly. On the fishing expedition itself I

didn’t catch anything but a sunburn. I’ve almost never caught anything fishing. Terry landed two albacore tuna,

which he left with his parents on the way back up to L.A.

Terry also had a

sister, who lived in some working-class suburb in the eastern part of LA

county. She was nice, but she didn’t smoke pot, and her husband was in some

kind of trouble. I never felt very comfortable when I drove Terry out there.

On the occasion of my

26th birthday, when Susannah threw my big 26-years-of-failure party, Terry

phoned me in the early afternoon, just after John Ware had left to go play

drums at the country-music bar in Glendale (leaving me a bit drunk), and

invited me over to the little bungalow he was sharing with Chris. Various

advanced books on calculus were lying around, along with sheets of paper

covered with symbolic calculations written in Terry’s crude hand with a dull

pencil. Out from between the pages of one of the math books he withdrew my

birthday present: a small amount of brown heroin that someone had smuggled to

him in prison, but which he’d never felt like taking. I snorted it up, but,

combined with all the other controlled-substance presents I got that day I

can’t say it, the one sniff of heroin in my life, was that noticeable to me.

When I left LA a few

months later we kept in touch for a while, Chris writing the letters for both

of them. They moved up to somewhere in Northern California for Terry’s further

studies in advanced mathematics, and got caught up in playing the well-known

university games: “fresh flesh” was the way Chris put it. The woman I was

married to by then wasn’t amused. She took it as an invitation to go look them

up and join them, and she destroyed all copies of their address, and that was

that.

Martin & Murray

Martin and Murray

lived in the first-floor apartment right next to Susannah’s at Bonnie Brae and

Kent in 1972. They were hard-drinking, upper-gulping, outlaw independent

long-haul truckers, not at all averse to driving the back roads so they

wouldn’t get weighed, and all that other subversion of ICC monopoly-protection

legislation. When Little Feat came out with the song Willin’, they loved it.

They shared a rig.

When Martin was on the road, Murray stayed in LA, and the other way around.

They usually weren’t both in their apartment at the same time for more than a

couple of days at a stretch, the first of these generally being party time, all

neighbours invited. For some reason Murray usually liked to cook salt pork for

these parties. Then it’d be time to wash and do maintenance on the rig, and

then for the other to head out.

Martin was a

Hungarian refugee. Martin Plavity. He was a good-looking guy with regular

features who wore his hair straight back. As he told the story, he’d been one

of those on the rooftops shooting at the Russian tanks in 1956. He’d managed to

escape to Italy, but he’d been thrown out of Italy for pimping. They couldn’t

deport him back to Hungary for humanitarian and political reasons, but England

had been willing to give him a go. He’d promptly gotten into some sort of

trouble there, I think it was pimping again, and the Poms had sent him to the

most staunchly anti-communist country in the world, and therefore the only

country willin’ to take him: the US of A. Southern California. The only place

for him.

Anyway, Martin

trained as a machine-tool grinder, and was proud of his absolute accuracy in

this skill. Once he showed me his kit of precision tools and told me about how

some of them required him to be accurate to something like one one-thousandth,

or maybe it was one ten-thousandth, of an inch. Alas, he also fell into pimping

again (I think he’d done some time for it, but had remained safe from

deportation). Then he’d met Murray and fallen for the lure of the open road.

Murray never told

anybody I knew if ‘Murray’ had been his first name or his last. He’d been a

math teacher in a small town in central California. He had a red-neck accent

and speech patterns, and, generally, a country, good-ole-boy way about him. I

thought all this was a scam, because once I got to know him he didn’t seem that

way to me at all. Well, not much. He seemed more like a former high school

teacher on uppers. Anyway, the classroom had been giving him claustrophobia,

and he’d taken to what looked to him like a life of freedom. I mean, long hours

in the cab of a semi could conceivably give someone — someone else, that is —

claustrophobia, I suppose. Not, however, Murray.

Usually.

He did tell me a

story about how he once scored a handful of black mollies (biphetamine

sulphate, I think 20 mg) from an acquaintance at a truck stop, swallowed them

down with his coffee, shared another joke or two, and then returned to his rig

and its load of fresh produce (in his trucker slang, “garbage”) bound for

Seattle. “I must have been 20 miles down Interstate 5,” he said, “when, I don’t

know, I just had to pull over onto the shoulder, stop, run around the rig ten

or twelve times, hop back in, and head on down the road.”

Bon appetit!

On the subject of bon

appetit: once when we were neighbours Murray met an old friend at a truck stop

who was driving a tank truck loaded with cheap brandy, and the friend had

offered to trade or give Murray some of it. The only problem was that Murray

had to provide his own containers. The only stuff in Murray’s load that was in

containers was cooking oil, so he’d dumped a couple of ten-gallon tins of oil

down the truck stop drain and filled them with cheap brandy tapped from the

tanker. And he brought it home. And he gave me a half-gallon wine jug filled

with this ghastly mixture of cheap brandy and little globules of vegetable oil.

And I actually tried to drink it! I

mean, as it turned out, I couldn’t drink it, but, heaven help me, I tried.

Murray had a girl

living with him. I’d guess she was about 20. Her name was Diane. He said she

was the daughter of a friend of his. She had an absolutely perfect model’s

face, but she was apparently what used to be called Not Quite Right In The

Head. Spooky, actually. Susannah told me that when Diane had her period she

used cloth diapers for feminine hygiene. Murray said he was taking care of her

for his friend. She usually rode with him when he was on the road.

When Murray wanted to

send me a message, or wanted to borrow something, he always sent Diane.

Susannah thought this was disgusting, manipulating me with her pretty face, but

I didn’t mind.

As the summer set in

and my economic condition became ever more perilous, Murray decided to teach me

how to be a truck driver. He took me with him once as he drove the rig down to

some produce-distribution centre in Orange County to pick up a load of ‘garbage’.

I remember trying to learn by watching how to shift through 15 gears while

driving, and it didn’t seem to be as simple as Murray said it was.

Rolling along the

freeway, Murray gestured toward the expanses of Southern-California residential

subdivisions stretching out into the distance, right and left, and told me,

“You know what those are? Concentration camps! And the people in them don’t

even know what they are! I’ll die before I’ll let anybody put me in one of

those!” Murray tended to end his spoken sentences with exclamation points.

At the depot Murray

backed his rig into one of the bays at the loading dock more quickly and easily

than I could have backed in my Ford Ranchwagon Six. I knew at once that backing

a rig up like that was something I’d probably never be able to do. We hosed out

the trailer, which had carried cedar shingles down from Seattle on Martin’s

return trip the week before, and loaded it with produce. The refrigerator unit

hummed as we worked, keeping things cold. I wondered at this trucking life.

Murray dropped me off

in Echo Park and picked up Diane for the drive North. I got a job offer from

John Kuehne in Texas soon afterward, so my training on the Big Rig ended before

it ever really began.

No comments:

Post a Comment